Features

Profiles

Frozen in time

The biological clock never ceases ticking, and all living things die. But that clock can be frozen, and decay curtailed indefinitely. The implications to fish conservation are large.

October 17, 2018 By Craig Springer

Dr. Wade Wilson

Dr. Wade Wilson Williams Creek National Fish Hatchery, situated amid the ponderosa pine-studded hills of the White Mountains of eastern Arizona, harbours gold: the only captive Apache trout broodstock in existence.

This hatchery, one of 70 national fish hatcheries, turns 80 years old this year. It’s a product of the New Deal era – a hatchery built on Apache lands under the auspices of the White Mountain Apache Tribe for the express purpose of raising trout for fishing. Trout fishing, then as now, helps fuel a rural- and tourism-based economy in the White Mountains.

Apache trout (Oncorhynchus gilae apache), odd as it may seem, is a fairly recent arrival to the hatchery given that it sits so closely juxtaposed to native trout habitats. Recognizing the trout swimming in their streams as something special, the tribe closed off reservation waters to fishing approximately 30 years before the Endangered Species Act became law in 1973. The tribe was the first conservator of Apache trout.

Though this rare trout wasn’t described for science until 1972, hatchery biologists made early attempts at creating an Apache trout broodstock. Getting wild fish accustomed to captivity is difficult. Those attempts fell flat until 1983, by which time commercial fish food had become more refined such that captive wild fish take to it easier. The existing Apache trout broodstock turns 35 years old this year. These captive fish are descended from the original fish brought on station more than three decades ago.

Boost from science

To bolster the broodstock, biologists have turned to what sounds like science-fiction: “cryopreservation.” It’s a big word for this: they collected sperm from wild Apache trout and froze them.

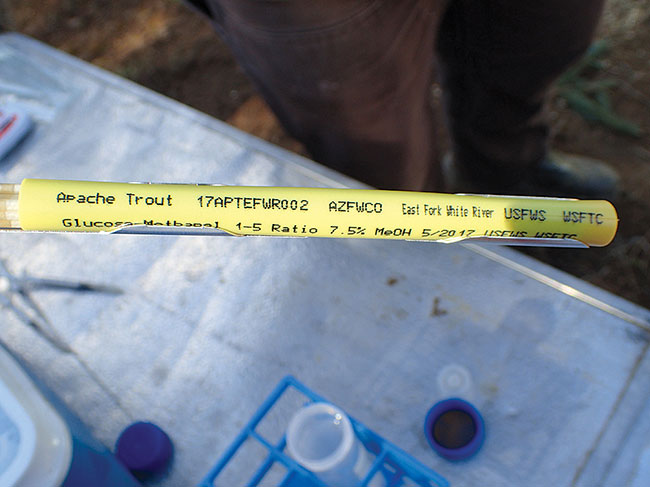

It’s science-fact. Hatchery biologists along with staff from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (Service) Arizona Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office and White Mountain Apache Tribe collected sperm from wild Apache trout from the East Fork White River. Under the guidance of Service biologist Dr. William Wayman at the Warm Springs Fish Technology Center in Georgia, the team of biologists collected and froze sperm from several individual Apache trout this past spring.

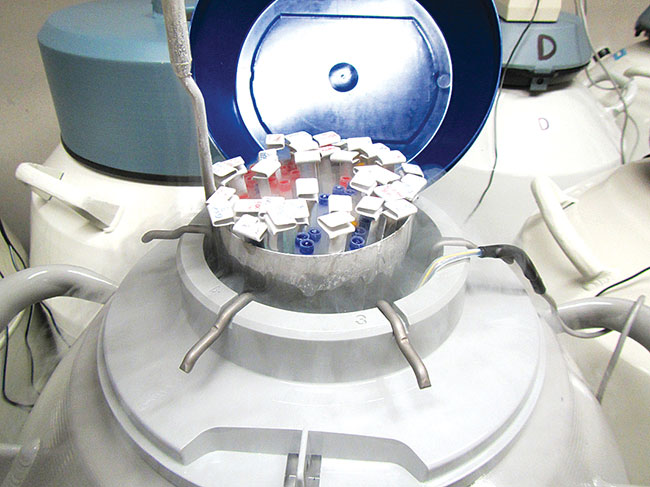

Gathered and stored in clear straws the approximate size of a coffee stirrer, the sperm now reside in vats of liquid nitrogen at -321°F (178.3°C) in a permanent storage in Georgia. And there it will stay until it’s needed for spawning at the hatchery in November.

“We expect cryopreservation to boost our broodstock,” said hatchery manager Bruce Thompson. “Cryopreservation reduces the likelihood of spreading disease that comes with having live fish brought in from the wild, not to mention the savings – a savings in space, in time and in money – by not having to keep wild male trout alive at the hatchery.”

The hatchery stock originated from the East Fork White River – it’s a rare lineage of a rare trout, says service geneticist Dr. Wade Wilson. He is stationed at the Southwestern Native Aquatic Resources and Recovery Center in Dexter, New Mexico. Wilson has expert knowledge of trout, having worked with two other species native to the American Southwest, the Rio Grande cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarki virginalis) and Gila trout (Oncorhynchus gilae).

It’s genetics

“Cryopreservation at least preserves the genetic diversity of the males, and the main advantage is that we can infuse wild genetics into the captive fish with great ease,” said Wilson. And the approach will be disciplined, as Wilson has developed a plan for the hatchery staff to ensure that each pairing yields genetically robust Apache trout offspring that exemplify the East Fork lineage. Having collected the genes from the wild male fish and the captive female Apache trout, data from Wilson’s shop will steer captive spawning this autumn. Those offspring will be future broodstock.

The whole idea of freezing and thawing a living organism gives flight to the imagination, even if it is a single cell. Cryopreservation has never been used for Apache trout broodstock management, until now, but the concept isn’t new. The method is common in the livestock industry and has been used for decades.

For rare, native trout, “it’s like backing up your data,” says Thompson. “You store off-site what’s precious, and we’re confident that this is good for Apache trout conservation.”

Craig Springer works at U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Southwest Region. You may contact him at craig_springer@fws.gov.

Print this page