Features

Breeding

shellfish

Small units, big impacts

Thanks to a new stacking system, hatcheries in the UK and North America are breaking new ground in overturning the declining number of lobsters in the wild.

September 20, 2023 By Bonnie Waycott

Lobsterman Michel Cyr is releasing trays attached to a longline to put them on the sea floor.

(Photo: Jean Côté, RPPSG)

Lobsterman Michel Cyr is releasing trays attached to a longline to put them on the sea floor.

(Photo: Jean Côté, RPPSG) The United Kingdom is seeing a crisis in the number of lobsters in its waters.

Lobster fisheries have long played a key role in local economies and fishing communities, but today, the species is fully exploited and at risk of collapse. The lobster most under threat is the European Clawed Lobster (Homarus Gammarus), while there is growing concern over the state of its sister species, the American Clawed Lobster (Homarus Americanus).

The reasons behind the declining number of lobsters are a multitude of issues from overfishing and continued fisheries mismanagement, to lobster habitat degradation, resulting in fewer lobsters that are able to reach adulthood.

Wild populations are also likely to be affected by climate change. For example, temperature changes in waters off the state of Maine have been blamed for a huge lobster migration to northern waters.

This situation is something that lobster hatcheries in the UK want to change, and fishing communities and organisations are now employing hatcheries to restock their regions and help the sustainability of catch numbers.

Captive breeding programs to rear the species before growing them in the open sea offer hope that stock enhancement could be significantly improved and lobster farming could provide new prospects for diversification and employment to fishing communities.

A pioneering new system

One technology that’s making significant contributions to lobster hatcheries is the Aquahive, produced by Ocean on Land Technology (OOLT), a developer of hatchery and industry-specific aquaculture systems in Northampton, UK.

Specifically designed to allow the rearing of large quantities of cannibalistic and predatory species like clawed lobsters, this proprietary juvenile system can be adapted efficiently and safely to meet hatchery requirements. From their controlled juvenile stage, the lobsters can then be transferred to sea for restocking programs around the UK.

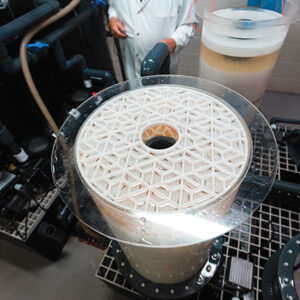

The Aquahive is a cylindrical container measuring 876mm high and 686mm wide. It was originally designed to enable higher survival rates of juvenile clawed lobsters to facilitate the transition stage between stages three, four and five of the rearing process (this traditionally carries a high mortality rate due to cannibalism). One Aquahive container can hold up to 3,780 lobsters in less than 0.5m<ss>2</ss> of floor space and comes with circular perforated honeycomb-shaped trays that are divided into individual cells. Each tray holds 140 juveniles, while the container can carry a maximum of 28 trays. Once in the containers, the lobster are weaned onto a formulated feed. Isolating individual clawed lobsters into their own cells greatly increases overall survival, reduces close proximity stress, and has been shown to increase growth and development compared to traditional mono-layered tray systems. It can also benefit other aquatic species that share similar biological characteristics and predatory behaviours to lobster. The Aquahive also comes with spare feed pumps and heavy acetyl and skeleton trays to release juveniles back into the wild with lower rates of predation.

“As well as housing many thousands of lobsters, the system also employs an automatic feeding system, which enables hatchery staff to feed their lobsters simultaneously without disturbing or stressing them within their trays,” said Stephen Allen, OOLT business development director “The tray system can also be adapted so that Aquahive can be used for non-aggressive species like crab, langoustine, spiny lobster species and even sea cucumber.”

Complex hatchery rearing

Producing juvenile lobsters in a hatchery is no easy feat. Wild-caught buried hens (females with eggs) are brought ashore under licence before being reared in a light and temperature-controlled broodstock unit that mimics the perfect habitat to bring on the release of larvae.

These larvae are then collected and moved to the juvenile part of the hatchery for the larval stages, which involve an upwelling system that keeps them slowly moving within the water column to prevent them from gathering and nipping at each other.

After the larval stage, they are moved to the Aquahive, where many thousands of juveniles are separated in a safe habitat so that they can develop further prior to being released into the wild.

One of the biggest challenges that a lobster hatchery faces is keeping the lobsters separate in order to maximise survival rates, said Allen. In the wild, the survival rate figure is circa one per cent. This is because during the larval stage the juveniles are planktonic and follow the currents, which means that predation is very high, but the Aquahive has given hatcheries survival rates of up to 58 per cent.

In other words, if one female releases 20,000 larvae, over 12,000 will reach stage five/six of the rearing process and be ready for release (in the wild, it is estimated that only one juvenile from a similar female would reach maturation).

Another challenge is releasing the lobsters safely.

“To start with, there were several release processes, including from accessible beach areas which, although easy to do, limits the geographic ability to release in deeper water offshore,” said Allen.

“From here, techniques such as pouring the lobster in at the surface and pumping them down to the seabed were also used but with limited success. This is because both processes require the lobster to pass through the water column and ultimately they can be picked off by fish. So, along with one of our hatchery owners in Canada, we came up with a release system using the trays that the lobsters are housed in within the Aquahive, with skeleton trays now being carefully lowered back into the wild, resulting in much lower rates of predation. This system is incredibly successful and our preferred mechanism for release to this day.”

Most major lobster hatcheries in and out of the UK are now using Aquahive. Jean Côté runs the Gaspe Bay Lobster Hatchery in Quebec. In 2010, the Regroupement des Pêcheurs Professionnels du Sud de la Gaspésie (RPPSG) began producing lobsters in a hatchery to release juveniles at sea and compensate for three to five percent of its fishermen’s annual commercial catches. In 2011, the RPPSG was the first in North America to use the Aquahive.

“This innovative system has several advantages,” said Côté. “It allows a larger production in a minimum space and time, and simplifies daily feeding of post-larvae in culture. In addition, releasing juveniles lobsters into the ocean directly in the Aquahive trays facilitates seeding logistics, reduces predation and gets fishermen involved, making them aware of the fragility of the resource. The first Aquahive we bought increased production from 20,000 to more than 60,000 lobster at stage five and above that were then released annually. Since acquiring a second Aquahive in 2017, we are producing more than 200,000 lobsters at stage five and above.”

Effective adaptation and new initiatives

Work is continuing to tailor Aquahive so that it fits hatcheries’ needs and delivers the best possible solution based on the number of lobsters that a hatchery wants to produce. From that number, the entire hatchery unit is designed, incorporating the broodstock, larval and grow-on stages within a single modular facility.

With the reported rise in sea temperatures and the effect that this is having on catch numbers in some regions, Aquahive can also be temperature-controlled so the lobsters can be reared in warmer temperatures. This means that when they are released into the wild, the warmer sea temperature is not a cause for concern.

Depending on hatchery feedback, other improvements can also be made, primarily with adaptation for use with other species and simplifying the rearing process in other shellfish species.

To date, OOLT has created custom solutions for 16 different species with no signs of slowing down. As Aquahive became more popular, the company realised that there was huge potential to offer more closely associated products to help protect wild lobster stocks, and came up with the Hatchery in a Box system, a containerised pre-built production system that can be customised and utilised for the production of various species. It occupies a small footprint and is fitted in one or more specifically-fitted-out sea containers of 20 feet or 40 feet that can be easily shipped around the world to coastal areas and harbours.

Meanwhile, the Aquahive trial system has proved popular with academic institutions that are looking to explore the production processes and requirements for new species where production knowledge is limited.

Allen is thrilled by the many possibilities opening up for lobster enhancement and aquaculture programs as a result of the Aquahive system.

“Its popularity has brought interest from institutions looking at developing systems to rear other predatory species like crab,” he said. “Aquahive is currently being used in trial systems for the production of king crab, snow crab, brown crab, dungeness crab and even crayfish. In the meantime, the hatchery in Gaspe Bay is pushing to double its capacity in the coming year because local fishermen are so pleased with the increase in catch numbers and the number of juvenile animals coming up in the pots. If the fishermen are reporting this, that is high praise indeed. It’s a very exciting time and we are looking forward to seeing what the future holds.”

Print this page

Advertisement

- Benchmark announces commercial team expansion

- Crab hatchery opens up in Florida for coral reef restoration