News & Views

Climate change threatens Great Lakes aquaculture, expert warns

March 11, 2025

By Hatchery International staff

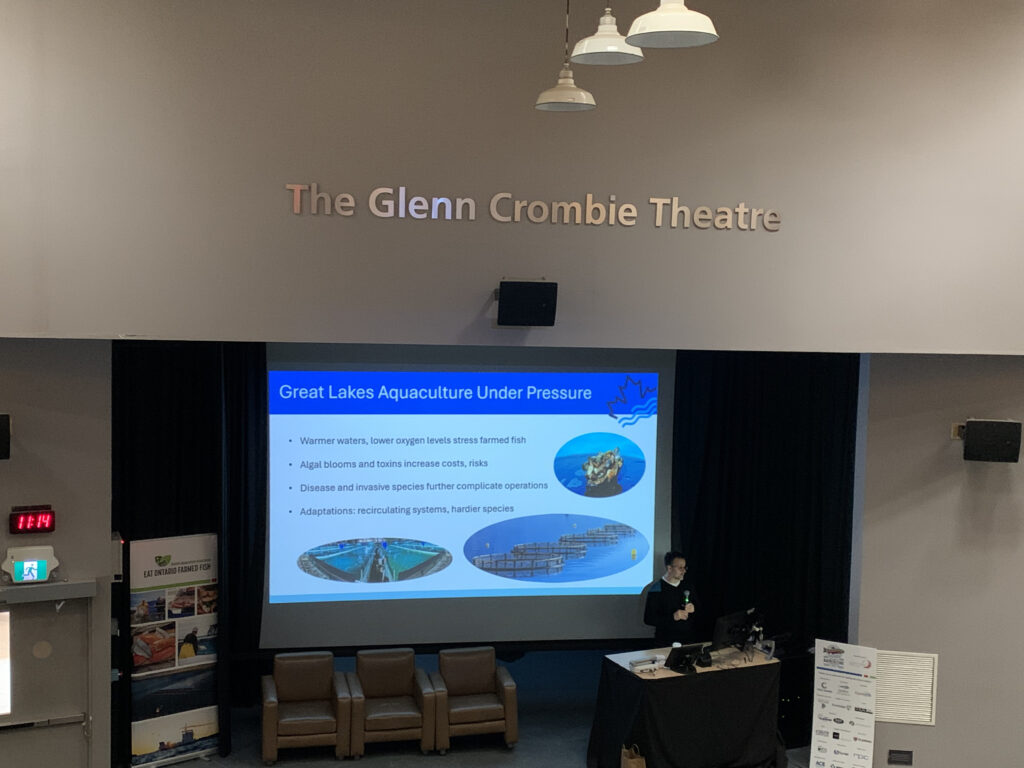

Luca Cargnelli, Great Lakes program coordinator at Canada Water Agency, at the 2025 Ontario Aquaculture Association conference (Photo: Seyitan Moritiwon)

Luca Cargnelli, Great Lakes program coordinator at Canada Water Agency, at the 2025 Ontario Aquaculture Association conference (Photo: Seyitan Moritiwon) Luca Cargnelli, Great Lakes program coordinator at Canada Water Agency, is saying Great Lakes aquaculture is under pressure.

The Great Lakes are not just bodies of water; they are a lifeline for 40 million people in Canada and the United States, providing drinking water and supporting fisheries. However, decades of industrial pollution, invasive species, population growth and urban development that came with it and habitat destruction have weakened the system and climate change is accelerating these changes.

Cargnelli gave a presentation at the Ontario Aquaculture Association conference at Lindsay, Ont., on Feb. 27, about Shifting Waters: Climate change and the future of the Great Lakes ecosystem. He said lakes are rapidly warming, with Lake Superior being one of the fastest-warming lakes in the world.

“Warmer water fuels more frequent and severe harmful algal blooms. Toxic cyanobacterial blooms in Lake Erie, for example, are capable of poisoning drinking water and are now an annual occurrence,” Cargnelli said.

Warmer temperatures and increased nutrient runoff from heavy rains are also making algae blooms worse and more frequent. Cargnelli said these blooms are made up of cyanobacteria, which thrive in warmer, nutrient-rich waters. They can contaminate drinking water, create death zones where oxygen levels plummet, and kill fish.

Cold water fish species like trout and whitefish are also struggling with warming waters, while invasive species like zebra and quagga mussels thrive in the changing conditions. But all the climate change models predict this warming will continue.

“Aquaculture holds immense potential that it will have to continue to adapt in order to thrive in the changing climate conditions,” Cargnelli said, adding that using recirculating aquaculture systems is a method of adapting to the changing climate.

He believes collaboration with researchers and government programs can help fund innovations and improve the long-term sustainability of Great Lakes aquaculture.

Pointing out some of the solutions to reduce nutrient runoff and prevent algal blooms, he said: Investing in green infrastructure and nature-based solutions that can handle extreme weather; Restoring wetlands and native fish habitats to increase the resilience of water bodies; Strengthening financial collaboration through mechanisms like the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement; Strong policy and collaborative efforts across all levels.

“By staying engaged, whether through the public forum, the financial committees or by getting engaged in local community science projects, you can help shape the policies and actions that will protect the Great Lakes for generations to come. If we care about the Great Lakes, now is the time to get involved,” Cargnelli concluded.