Features

Breeding

Hatchery Operations

Research

The world’s first octopus farm

Nueva Pescanova’s octopus farm opening soon

May 4, 2023 By Treena Hein

Nueva Pescanova’s research centre in Galicia.

Photos: Grupo Nueva Pescanova

Nueva Pescanova’s research centre in Galicia.

Photos: Grupo Nueva Pescanova After decades of research conducted in many locations around the world to crack the mystery of octopus reproduction in captivity, recent breakthroughs in Spain are allowing a company there to open the world’s first commercial octopus farm in the near future.

Grupo Nueva Pescanova, headquartered in Galicia, is set to begin farming the most common octopus eaten in Europe and beyond, Octopus vulgaris. According to the company, it is also the most common octopus species harvested throughout the Mediterranean and the Atlantic Ocean.

The research was conducted at the Spanish Oceanographic Institute (Instituto Español de Oceanografía, IEO). It is here where scientists in 2018 announced they found a successful method for octopus born in aquaculture to reach adulthood and reproduce. In 2019, the institute patented its method and reached an exclusive patent agreement with Nueva Pescanova, where research now continues.

The company’s principal cephalopod researcher, Ricardo Tur, explained on the Nueva Pescanova website that octopuses are organisms that, even in the wild, require very specific conditions for development – the right temperature, salinity, current levels and so on. In fact, the survival rate of a wild octopus is 0.0001 per cent.

The studies initiated in 2005 by the IEO of Vigo and the Moaña octopus fattening tank, focused on achieving optimal culture densities, as well as improved understanding of the conditioning factors that affect the feeding and biology of the species, have allowed Nuevo Pescanova to obtain survival rates at the end of fattening of 96-97 per cent in 2022.

In terms of basic octopus biology, the lifespan is between two and three years. Females lay eggs in the environment and tend them for about a month until they hatch.

Controversy looms

Protests against octopus farming have been significant and has involved both animal rights groups and scientists over many years. On World Octopus Day (Oct. 8) last year, protests were held around the globe focused on pressuring the Spanish government to shut down Nuevo Pescanova.

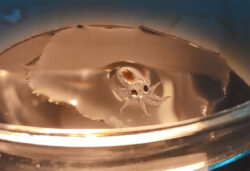

Octopus paralarvae

Britain’s state-sponsored news outlet, BBC, claims to have documents showing Nueva Pescanova will kill octopuses in an ice slurry. The BBC quotes Prof. Peter Tse, a cognitive neuroscientist at Dartmouth University, saying that this type of “slow death… would be very cruel and should not be allowed.”

Jonathan Birch, associate professor at the London School of Economics, published a review of more than 300 studies which show that octopuses feel pain and pleasure. The species is therefore recognised as “sentient” in the UK’s Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act 2022.

In the US, the State of Washington has proposed a ban of octopus farming. In Hawaii, the Kanaloa Octopus Farm has been accused of cruelty and was recently ordered to discontinue its activities by the state government due to not having the correct permits. The farm’s owner has stated the permits in question do not apply to his activities, but that the farm will cease octopus breeding for now and apply for the permits in question.

Sensitive transition

When Grupo Nueva Pescanova moved forward with the research, its scientists focused on developing a viable protocol for rearing octopus as what’s called the “settlement phase” of the juvenile’s life ends and the benthic stage begins.

This was the most difficult challenge, explains David Chavarrías, director of the company’s research arm, Pescanova Biomarine Center, because octopuses undergo major physiological and behavioural changes during the transition to a benthic lifestyle. Until now, researchers have been unsuccessful with getting them through this phase, experiencing very high mortality rates.

However, Nueva Pescanova’s researchers say they’ve found a solution. “The main innovation in the breeding of this species was to improve the management of the tank environment, not only in terms of water quality, but also in terms of light conditions and water currents,” says Chavarrias. “At the end of the research process, our team reached a high level of expertise, enough to complete the process and leading us to good survival rates.”

Teasing apart life stages

In order to ramp up the scale of the larval cultures, the Nueva Pescanova researchers also needed to closely examine each phase of development. “As an example of our progress, we can now identify four to five different stages in the life of octopuses before they reach their juvenile stage,” says Chavarrias.

These phases are not only defined by morphological changes, but most of them, he explains, are defined by changes in behaviour.

“Proper adjustments to the tank and culture conditions between these different phases are vital for the proper development of pre-benthonic and early-benthonic octopuses,” says Chavarrias. “Our advances solve this bottleneck by rearing individuals that meet their needs in terms of diet, water quality, tank environment and welfare.”

While the company cannot share further details of the tank conditions or details of the tanks themselves, Chavarrias can say that the early life stages “are so sensitive to stress factors that guaranteeing their well-being is key to end a successful culture.”

“We are fully committed to the animal welfare and, in this sense, we are promoting several welfare studies around this species, specifically aimed at finding the physiological basis of their stress response systems,” he adds.

The challenges of maintaining the system for octopuses are very different from those faced by fish farmers, Chavarrias explains, mainly due to the ammonia metabolism of octopus and the rapid replacement of their sucker skin.

“Because of these characteristics, the waste produced by octopus is too much for mechanical and biological filters to handle,” says Chavarrias. “As a result, we had to modify the recirculation system using certain proprietary technologies.”

Print this page

Advertisement

- Whirling disease discovered in New Mexico hatchery

- California tribe partners with state hatcheries to save endangered salmon