Features

Breeding

Hatchery Operations

shellfish

The oyster choice

Triple N Oyster Farms is determined to build the U.S. oyster aquaculture industry

November 24, 2022 By Treena Hein

Steve Pollock is owner and operator of Triple N Oyster Farms in Baton Rouge, La., USA. (Photo: Triple N Oyster Farms)

Steve Pollock is owner and operator of Triple N Oyster Farms in Baton Rouge, La., USA. (Photo: Triple N Oyster Farms) To say the oyster industry in the Gulf Coast of the U.S. has had a difficult last three years would be an extreme understatement. But companies like Triple N Oysters of Baton Rouge, La. are doing their best to give it a solid future.

“Over the last few years, both the off-bottom (alternative oyster culture or AOC) farms and the conventional bottom farmers were devasted by two hurricanes, Zeta in 2020 and Ida in 2021,” says Dr. Steve Pollock, owner of Triple N Oysters, current president of the Louisiana Oyster Aquaculture Association and a voting member of the Oyster Task Force, an oyster industry advisory group of the Louisiana Department of Wildlife & Fisheries.

“In 2019, we also had a record flood of the Mississippi River and this lowered salinity, which also negatively affected oyster production in Louisiana,” he says. “And of course, the restaurant and tourism closures of the pandemic have also devastated this industry.”

But even before all this, oysters were struggling to survive and reproduce in the Gulf coast states, down into Mexico and up into Canada. Lower oxygen levels and acidification of water are some of the suspected factors, as are emerging pathogens and swings in salinity levels. No one answer has been found, and Pollock notes that every state of the Gulf Coast has its own unique issues.

“There’s too much salt in Florida seawater for example,” he says. “I think pollutants are also a factor in Louisiana. We do a lot of spraying for mosquitos here. I call oysters the canary in the water. They are very sensitive to water quality.”

After his PhD (on algae biology) and while working at Louisiana State University, in 2015 Pollock and his wife started an AOC farm off the coast of Louisiana near Grand Isle. They sold many oysters to restaurants in the Baton Rouge area.

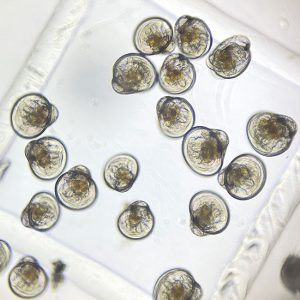

“Then there was a seed shortage, so we started a nursery,” he says. “It went well. We sold seed up and down the coast, but then we couldn’t get enough larvae from the state-run hatchery. So we decided to start our own RAS hatchery in 2018. We use our own artificial seawater, so we are not affected like hatcheries that use seawater, by the salinity levels swings that affect the coast of Louisiana, due to the varying volumes of the Mississippi River, currents and weather. Salinity is a big factor in oyster production. If salinity is too low, they will not reproduce and there is also some adult mortality.”

Oyster choice

The “Triple N” in the company name refers to the ploidy of the oysters. Pollock sources from 4Cs, which has a monopoly on licencing tetraploid oysters in Louisiana, across the U.S. and beyond. Triple N oysters result from crossing tetraploid oysters with diploid. “They’re almost all sterile and don’t waste resources reproducing,” Pollock says, “so they are much fatter through the summer months.”

Like other hatcheries, Triple N mostly sells to AOC operations, about 25 right now and mostly beginners in the industry.

In this type of production, oysters are grown in cages suspended near the top of the water column. The density must be thinned over time and market size is achieved in about a year. This is much faster than conventional farming, where crushed concrete or limestone is placed at the bottom of the Gulf (millions of dollars is spent on this every year), the beds are tended and market size is achieved in two to three years.

“AOC oysters are generally called ‘boutique’ oysters and they are marketed with other names in a wide variety of ways,” says Pollock. “They are a premium product and get more money than conventional, but I’m not sure how much right now. There are a lot of supply and demand issues with everyone recovering from the hurricanes and COVID-19.”

AOC oysters receive more oxygen and algal concentrations being at the top of the water column. The constant rocking action of the waves generates a deep cup. Pollock says they have a uniform shape, are very pretty and taste great.

And although Pollock says AOC production could be developed to form a considerable amount of production in the state, it can only produce a fraction of what is produced conventionally.

“And right now, conventional production is less than five per cent of what it’s been over the last thirty or forty years,” he explains. “There is money to be made in oyster production, but newcomers to conventional or AOC don’t have the deep pockets that long-established farmers still have, and won’t be able to financially withstand a hurricane.”

Projects

Like other hatcheries, Pollock also sells into the coastal restoration project market. These projects are aimed at improving water quality in the Gulf Coast and oysters are a top project priority. Oysters filter water and remove large amounts of nitrogen. Oyster beds also serve as nurseries for crabs and many other species, and act as hurricane buffers to protect the coastline.

“There has been millions and millions of government money spent on restoration projects involving oysters in all states along the Gulf coast,” says Pollock. “It really took off after 2010, when BP was fined billions for a major oil spill. A lot of this money was earmarked for these restoration projects and there’s still lots of money available for them.”

Concern over getting funding could have been an issue when Pollock decided to situate the hatchery inland in Baton Rouge to avoid the threat of hurricanes and lost some investors.

“We weren’t considered a coastal interest and perhaps there was concern that we wouldn’t be eligible for funding because we moved inland,” he says. “But we have survived because we weren’t on the coast and therefore didn’t get hit by Ida. We remained in operation and were able to get farms along the coast going again to the extent they have been able to do so because we moved away from the coast – and also supply coastal restoration projects.”

Current production

Last year, Triple N produced just over 100 million larvae. Pollock also has a small experimental nursery which he hopes to expand.

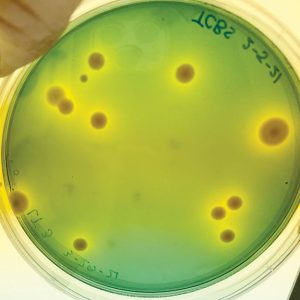

Hatchery production under the RAS system this year, however, has struggled, not in terms of steady temperature and salinity control but in terms of bacteria.

Pollock is using ozone and UV to destroy bacteria and is adding various strains of beneficial bacteria back to the sterilized water. “I am working with my current business partner, who is a microbiologist at Louisiana State University,” he says. “We purchase strains of good bacteria and also culture our own when we have a good batch of larvae. We also get them sequenced to identify them. But it’s proving very challenging to get the right microbial community. There are so many variables and they are very hard to control. It’s the hardest lesson I’ve ever learned, that living things are not that easy to control.”

December decision

Looking to the future of oyster production in his state, Pollock notes that in December, the government of Louisiana will make an important decision.

“The state has been planning on spending US$2 billion to divert the Mississippi River to prevent additional land loss,” he explains. “Constant coastal erosion is a big problem due to the levy on either side of the Mississippi that was built long ago to keep the river deep enough for shipping. But diverting the river will cause a salinity drop that will make entire areas of the coast unfarmable for oysters. They will die within 30-60 days. They can’t move like shrimp and crab and fish. And this diversion will only create 21 acres of land over a timespan of 50 years. So, it’s controversial to say the least.”

Print this page