Features

Breeding

Genetics Week

Research

shellfish

Te Huata’s mussel spat hatchery strengthens New Zealand industry

A new hub for mussel production and a significant venture for the Te Whānau-ā-Apanui

May 25, 2023 By Bonnie Waycott

Photos: haydn read, Te-Whanau-a-Apanui Mussel Hatchery

Photos: haydn read, Te-Whanau-a-Apanui Mussel Hatchery Mussel farming in New Zealand is worth US$380 million a year, but one new hatchery is going to be more than part of a thriving industry.

Last year, the New Zealand government announced plans for a green mussel spat hatchery near Te Kaha, in Te Moana-a-Toi Eastern Bay of Plenty, to help the Indigenous tribal nation of Te Whānau-ā-Apanui develop the knowledge and rearing processes critical for successful mussel farming. Those involved hope that the Te Huata Mussel Spat Hatchery will alter the course of an industry that is reliant on wild spat and do much for the Te Whānau-ā-Apanui people, who have been dependent on the natural environment for food and resources for generations.

“The mussel spat that feeds farms in this country comes from the wild in Te Oneroa-a-Tōhe, or Ninety Mile Beach, in the north of New Zealand,” said Haydn Read, board member of the New Zealand Chambers of Commerce Eastern Bay and spokesperson for the Te Hēteri, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui project.

“However, wild spat doesn’t guarantee a continuous supply, and the mussel industry has been hurt on a couple of occasions. In certain seasons, supply doesn’t meet demand, while moving spat into different waters results in a high mortality rate. One of our goals with this new hatchery is to reduce the mussel industry’s reliance on wild spat, but we also want to generate wealth, wellbeing, and a better standard of living for the Te Whānau-ā-Apanui iwi. The project is very tightly coupled with the iwi’s historical connection to the sea.”

Self-sufficiency and more

The Eastern Bay of Plenty is one of the most deprived regions in New Zealand, and the Te Whānau-ā-Apanui iwi (tribe), consisting of around 15,000 people and 13 hapu (sub-tribes), which have struggled for generations.

Surveys from 2018 show that they are more socioeconomically deprived than New Zealand as a whole, and little has changed in the last two decades, largely due to the lack of employment. The tribe’s vision is that not only will the hatchery provide high quality mussel spat to meet present and growing demand, but also secure their livelihoods into the future.

Surveys from 2018 show that they are more socioeconomically deprived than New Zealand as a whole, and little has changed in the last two decades, largely due to the lack of employment. The tribe’s vision is that not only will the hatchery provide high quality mussel spat to meet present and growing demand, but also secure their livelihoods into the future.

“The iwi (tribe) members are very clear that through the hatchery, they want to create a pathway for people to come back,” said Read. “What captures their imagination is having jobs for kids, having purpose and being able to bring people home… About 90 per cent or more of their people don’t live inside the boundaries of their landmass, and remaining members are seeking to build capability among themselves. People would come home tomorrow if they had a job, but a job means full employment.”

“The iwi also has huge knowledge around plants and the environment for medicinal purposes and a whole raft of other things,” Reed continued. “It’s interesting that with this new hatchery, some of these cultural manifestations that have been around for generations are being combined with science to get a better outcome for all. Also deeply connected to the iwi’s thinking is environmental sustainability, that the hatchery is not extractive, it’s complimentary. That is deeply embedded in their stories.”

Strength and support

The Te Whānau-ā-Apanui iwi has joined forces with Aotearoa Mussel Limited, which will exercise the investment in practice. The joint venture will build the hatchery and research facility, and supply spat to the New Zealand mussel industry. Also on board is the Cawthron Institute in Nelson, New Zealand’s largest independent science organisation. Cawthron is partly funded for the project by Callaghan Innovation, a central government agency that supports opportunities like the new hatchery project, while other agencies such as Kānoa, the New Zealand Trade and Enterprise and the Ministry of Social Development have also offered support. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the team made the most of the lockdowns by focusing on hatchery design and work such as geotechnical reports, environmental surveys and cultural values assessments. Today, preliminary work for the right to build is now over, and the detailed hatchery design is underway prior to the application for building consent.

“The most specific objective of our research with Cawthron is to get a detailed understanding of two critical things,” said Read. “The first is producing mussel spat at pace and scale, and the second is redesigning how we want to build a mussel spat hatchery in this country with a focus on production principles.”

A world-class hatchery

The New Zealand government has set a goal for aquaculture to reach NZ$3 billion (US$1.9 billion) in exports by 2035. Nonprofit membership association Aquaculture New Zealand has indicated that the New Zealand green mussel industry has the potential to provide up to a third of this goal. A reliable source of quality hatchery-raised juveniles will be an important step in helping New Zealand’s aquaculture be more resilient, improving its supply chain and securing its long-term sustainability.

The new hatchery is expected to provide at least 10 per cent more selectively bred spat into the New Zealand marketplace. This spat will be evolved to mature faster, with a greater tolerance to changing global climate conditions. In parallel with the hatchery development, a breeding programme has been initiated so that once the hatchery is up and running, there will be improved broodstock available at the earliest opportunity, says Nick King, senior aquaculture scientist and project lead at Cawthron Aquaculture Park.

The new hatchery is expected to provide at least 10 per cent more selectively bred spat into the New Zealand marketplace. This spat will be evolved to mature faster, with a greater tolerance to changing global climate conditions. In parallel with the hatchery development, a breeding programme has been initiated so that once the hatchery is up and running, there will be improved broodstock available at the earliest opportunity, says Nick King, senior aquaculture scientist and project lead at Cawthron Aquaculture Park.

“At this stage, there are multiple breeding objectives and broodstock is being sourced from a range of populations to ensure that they have the greatest coverage of appropriate genetic diversity to feed into the breeding programme,” he said.

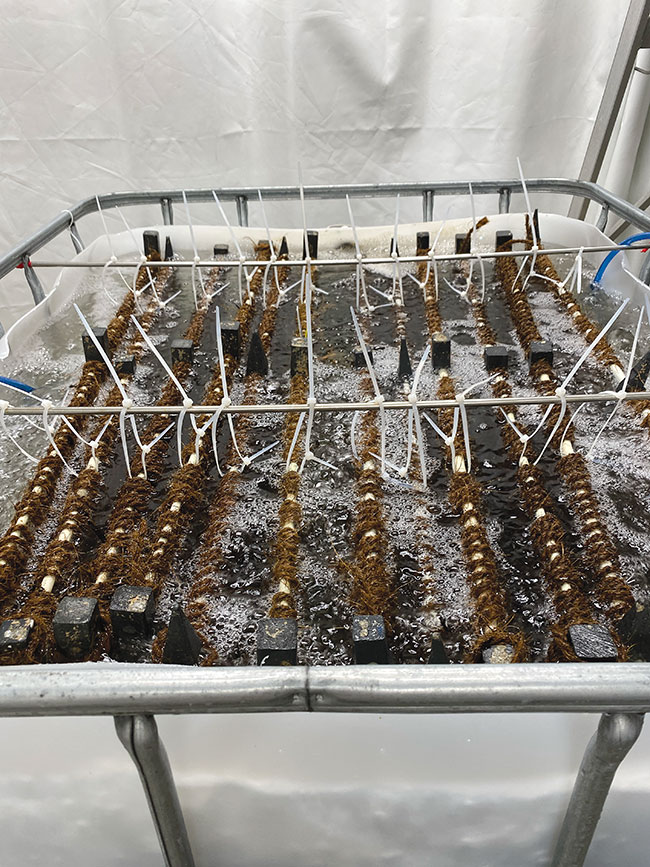

Hatchery production and capability in New Zealand tends to focus on high-density, continuous larval rearing, and work has been underway to develop and adapt these methods to suit the hatchery’s requirements, says King. The continuous larval rearing process utilises continuous feeding with classical live micro larval feeds produced using a mix of hanging bag and carboy production. Photo bioreactors are also likely to feature in the new hatchery. Typical larval densities will be in the hundreds per ml, with direct settlement onto rope substrate as larvae reach metamorphosis. Water quality at the new hatchery site is normally excellent, says King, but a lot of thought is being given to risk mitigation tools like buffer storage for the rare occasions when a seawater supply is unavailable.

“When developing a new hatchery, the top four things that must be taken into account would be access to clean seawater, a skilled and motivated workforce, biosecurity freedom to operate and services such as power, communication and freshwater,” said King. “Location is also key. This new hatchery will be in Te Whanau ā Apanui rohe, where the seawater is typically very high quality, deep and clear rather than muddy or estuarine. It’s also in the same region as several other aquaculture-related initiatives that are underway, such as port development at Opotiki, a new mussel processing plant at Opotiki and Whakatohea Mussels farm development in the Bay of Plenty.”

Developing the methods and capability to run a commercial-scale hatchery has been a steep learning curve, says King. Cawthron have provided the fundamental knowledge to get started and the facilities for staff to “learn by doing.” The goal is to help de-risk the hatchery development process and ensure that the capability is ready to go once the hatchery is built, he says. So far, the team has learned very quickly how to produce near commercial-scale larval batches, which has built confidence and been critical for informing the design and scale of the new hatchery.

Sights on the future

Today, New Zealand’s mussel industry is thriving, and despite the COVID-19 pandemic and associated market failures, it has continued to deliver growth and is being recognised for its export value. Hopes are high that the new hatchery will not only build knowledge and capability of mussel spat rearing, but also give a purpose and imperative to the Te Whānau-ā-Apanui iwi.

“We love doing this kind of work as it aligns with our organisational objective to apply our knowledge in ways that support iwi aspirations, whether they are seeking environmental, community or economic outcomes, or all of the above,” said King. “This partnership approach ensures that our research delivers the greatest possible impact. The Maori worldview has a lot to offer that everyone could benefit from, and that perspective is being embraced within this work. There is no one-size-fits-all approach. It’s a collaborative process and we are really enjoying working through this with the awesome staff from Te Whānau-ā-Apanui.”

Print this page

Advertisement

- Benchmark Genetics Chile receives disease-free certification for salmon eggs

- Hatchery 101: Energetic panel share expertise in efficiency