Features

Breeding

Profiles

Success with sablefish

With a Best Choice award under its belt, Gindara Sablefish on Canada’s Vancouver Island continues to dedicate its efforts to culturing a unique and unusual species

January 15, 2021 By Bonnie Waycott

(All photos: Gindara Sablefish)

(All photos: Gindara Sablefish) Found throughout the Pacific Ocean, sablefish (or black cod) has a rich, buttery flavour and dwell near the bottom of the ocean during their adult life. They feed on nutrient-dense fish such as pollock, herring, Pacific cod, jellyfish and squid.

In British Columbia, Canada, wild sablefish have been harvested off the west coast for many years. But commercial sablefish farming was only initiated about 15 years ago to fill a niche in the market for farmed, native species white fish that’s also well-suited to sushi. Today, sablefish aquaculture is a key industry in British Columbia where farming the species is quickly becoming a sustainable model.

Gindara Sablefish in Kyuquot, northwest Vancouver Island is the only one that’s producing sablefish at a commercial level. Established in 2007 and branded as Gindara Sablefish in 2014, the farm exports primarily to Japan (almost half of its production volume), the United States, several countries in Europe, and supplies a domestic market in Canada. And thanks to its cold, clean water and brisk tidal flow, Vancouver Island offers the ideal environment for sablefish farming.

“Our main customers are sushi restaurants and white tablecloth restaurants,” says Claire Li, sustainability director at Gindara Sablefish. “Our sablefish are particularly suited to sushi restaurants because they’re the only sablefish that can be eaten raw without freezing due to their commercial feed diet. This ensures that they ingest no live parasites, unlike fish that feed from the ocean food chain.”

Broodstock to juveniles

Gindara Sablefish’s hatchery is where it all begins.

The hatchery has a dedicated recirculating aquaculture broodstock system, incubation and early larval rearing stages, and a facility for fry grow-out and transportation staging. Approximately 80 per cent of the hatchery’s broodstock are wild B.C. sablefish.

The remaining 20 per cent are the F1 progeny. All broodstock are kept at very low densities and maintained in environmentally-controlled tanks. This ensures that temperature, photoperiod and salinity can be controlled precisely in order to aid in proper egg development.

“In this way, we can mimic natural spawning conditions as accurately as possible,” says Li. “Egg incubation is also temperature and salinity controlled, and in total darkness. Ponding is determined by degree days.”

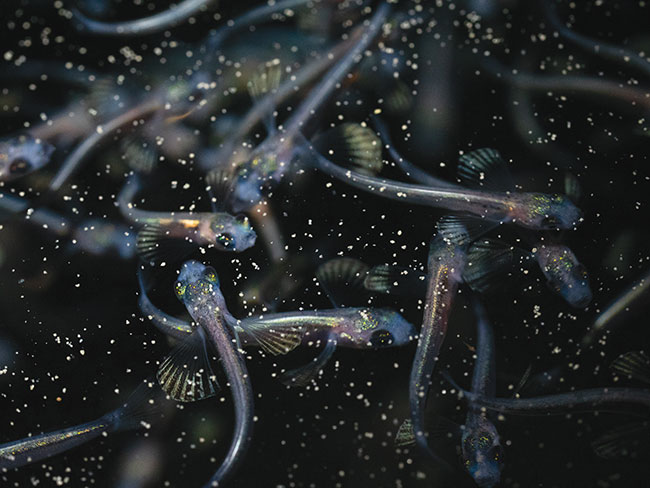

Eggs are held in incubation for up to 50 days before they are transferred to photo-controlled larval tanks with green water. At this stage, live feed of rotifers and artemia are cultured and enriched at the hatchery and fed throughout the larval stage.

Later, the fry are able to consume a dry, micro-diet. Standard water treatment is applied to all water at the hatchery using ozone, UV and filters. Once on dry feed, and once they reach 30 grams, the fry are held until they’re transferred to grow-out facilities.

Grow-out

Gindara Sablefish has two farm sites off the coast of Kyuquot Sound. One is comprised of eight open net pen cages and the other of 12. All cages extend to a depth of 125 ft. The ocean floor is at 350 ft.

As sablefish are cultured in their native environment, the necessary parameters are those that are already present in the ocean. Stocking density is kept low at 8 to 10kg/m3 to give the fish plenty of space.

Feed is comprised of wild forage fish (anchovies, menhaden), fish byproducts (hake, pollock), land byproducts (poultry, porcine sources), plant proteins such as wheat, corn, peas, beans and seeds, along with vitamins and minerals. Feed is pumped underwater using automatic feeders so the adults are fed at depth, as sablefish are a groundfish species that don’t usually come to the surface.

“The fish are then harvested at two sizes: 4 to 6lbs and 6 to 8lbs,” says Li. “They spend about three months at the hatchery and another 20 months in the net pens. In all, they take approximately two years to grow to harvest size.”

Quality control is assured, while industry-standard biological protocols are used during all stages of the production process. All government-mandated standards and internal standards for areas such as size, colour and quality are also met.

Pioneers

Because it’s a new aquaculture species, says Li, one of the most difficult aspects of growing sablefish is pioneering the research and development of a cold-water species.

For the hatchery team in particular, developing its own nutritional protocols, such as determining the crucial life stages and their nutritional needs, has also been difficult. But by working with the fish every day, the team has developed new techniques to build on its knowledge.

“Since we were the first to produce commercially-viable farmed sablefish, the staff at the hatchery pioneered the research and development necessary to take the wild sablefish species and make it suitable as a commercial farmed fish,” says Li. “Our understanding of salmon aquaculture was used as a baseline, and the methodology was gradually tailored to sablefish. Of note, the larval stage of the fish was the most challenging in closing the loop on sablefish culture.”

For the hatchery, other than producing a new commercial species, understanding the lifecycle and growing needs of sablefish in a controlled environment has been an invaluable addition to the team’s knowledge of the species within the scientific community.

To that end, the hatchery has collaborated with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) on sablefish aquaculture research for knowledge sharing. The company has shared written papers on various aspects of sablefish culture. They’ve also collaborated with the Vancouver Island University to offer co-op positions to aquaculture students so they can gain hands-on experience working at a sablefish hatchery.

“The hatchery’s success in rearing sablefish up to their juvenile stage allows the grow-out farm to continue the process and produce what is ultimately a Gindara Sablefish,” says Li. “Without the efforts of the hatchery, the farm would not exist and neither would its partnership with the Kyuquot-Checleseht First Nations.”

Bright future

In June 2020, Gindara Sablefish made headlines when it was awarded a Green, Best Choice seafood rating from Seafood Watch, Monterey Bay Aquarium’s sustainable seafood program. In a press release, it described the rating as “an objective measurement of Gindara Sablefish’s operations that defines the seafood as well-managed and caught or farmed in ways that cause little harm to habitats or other wildlife.”

Hot on the heels of the award, Gindara Sablefish is building on its experience by coming up with new, innovative ideas including sustainable packaging, and is looking to the future with optimism.

“One thing we’re excited about is a move to an eco-friendly box in which our fish are packaged,” says Li. “Reducing our footprint by using compostable packaging is a change we’d like to make.”

Print this page

Advertisement

- Philippines wild-caught crablet regulations to aid conservation bid

- Billund nets deal to build RAS for Mowi’s Norway farm