Features

shellfish

Sustainability

Saving the scallops

U.K. hatchery promises sustainable, ocean-friendly production

January 17, 2020 By Bonnie Waycott

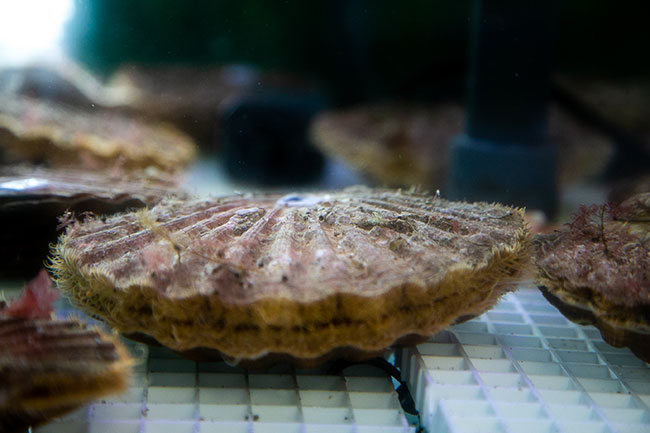

All photos by Ocean Conservation Trust

All photos by Ocean Conservation Trust

A new scallop hatchery in Plymouth, U.K., is hoping to ease the pressure from commercial scallop fishing, which has caused significant strain on the ocean and the species that end up as bycatch.

To offer a sustainable alternative to wild-caught scallops, UK charity the Ocean Conservation Trust and Plymouth Marine Laboratory (PML) set up the scallop hatchery in Sutton Harbour, which supports around 600 jobs and sells over 6,000 metric tons of seafood products, including scallops, each year to local restaurants and fish markets.

“Our aim is to establish a local, sustainable fishery that consistently produces viable King scallop (Pecten maximus) seed that will contribute to the reduction of destructive fishing methods and conserve this valuable species,” says Jessica Harvey, hatchery technician at The Ocean Conservation Trust.

A variety of scallops live in UK waters, in particular off western Scotland where commercial scallop fishing took off in the 1930s. In England and Wales, it occurred on a smaller scale until the 1970s, when landings increased thanks to the development of overseas markets. Today, many different scallops are widely sold by quality fishmongers.

However, scallops are mostly harvested by dredging, which results in severe ecological effects. Unless it’s managed effectively, the procedure can be extremely destructive due to problems such as bycatch and damage to the seabed. Bycatch include monkfish, dover sole, crabs and other benthic epifauna, while organisms can also be damaged from within the dredge bags due to abrasion from other organisms or debris. Despite efforts to return bycatch, those that are put back may die from physical damage, stress and vulnerability to predation.

New steps

The hatchery uses a small-scale recirculating aquaculture system with two broodstock conditioning tanks, six larval rearing vessels and two settlement tanks. There is also an algal culture facility containing around180 liters of live algae with a maximum capacity for approximately 200 liters.

“Ultimately, we’re aiming to produce as many scallops as we can support,” says Harvey. “Our settlement tanks can support a maximum of 480,000 settled spat, but at this stage we will not be stocking to our maximum capacity due to space restriction for grow-out. Additional space for early spat grow-out will be obtained if necessary.”

Broodstock

Broodstock are above the minimum U.K. landing size of 100 millimetres. Divers collect them by hand within marine protected areas off Plymouth and surrounding Drake’s Island. Both locations are within close proximity to the hatchery. They’re held in natural filtered seawater at a minimum of 30 ppt.

Water is changed daily due to the high bio load within a recirculation system. In the morning, 50 percent of a mixed algae diet is given, followed by another 50 percent in the afternoon. Feed quantity varies between 4 x 109 to 8 x 109 cells per scallop per day, depending on the stage of the conditioning regime. Eighteen adults are held in a 240-liter tank, below maximum density to ensure minimum stress levels.

This scallop hatchery was established in a bid to reduce the destructive effects of commercial fishing and offer a more sustainable and ocean-friendly alternative to wild-caught scallops.

Initial growth

Spawning is usually induced by a combination of thermal cycling, air exposure and the presence of fresh gametes in the water. Prior to spawning, natural conditions are mimicked through temperature and food increases, while staff are also looking closely at lighting regimes to mimic natural conditions even more.

Eggs are fertilized within a maximum of one hour of being expelled to ensure maximum viability, with trochophore larvae usually observed around 24 hours post fertilization at temperatures between 16 and 17 degrees Celsius. Larvae culture occurs in six 60-liter conical vessels. Containers with a large bottom surface area are used for smaller scale spawning.

“Larvae densities within these will vary, with an initial maximum of ten larvae per ml,” Harvey explains. “This number will decrease as they develop through their life stage. At settlement, a maximum stocking density of five larvae per ml will be used. It takes between 25 and 30 days post fertilization for settlement to begin, and metamorphosis occurs between five and 15 days, depending on environmental conditions. Our aim is to rear the larvae without any antibiotic treatment.”

A mixed algal diet is offered as feed. Microalgae cell densities are maintained between 20 and 50 cells μl-1. The cell density of the larval vessels is calculated twice a day for assessment and readjusted when required. The scallops are given a nutrient-rich single species for their first feed, before a mixed diet is introduced within a few days of them developing into straight-hinged veligers.

“It’s possible to use a single algae species if it contains the correct nutritional values,” Harvey says. “But this can vary depending on the environmental conditions. We opt for a mixed species diet so that the key components are delivered in abundance and will be continuing our work to establish and research a suitable mixed algal diet.”

Biosecurity

A strict biosecurity protocol is also in place.

“The hatchery will use natural seawater, which is exposed to a four-stage filtration process before it reaches the hatchery system,” Harvey explains. “It’s drawn in from Plymouth Sound, passed through a sand filter, treated with ozone at 750 millivolts, passed through a UV system and held within our storage tank until it’s required for use. This process takes a minimum of four hours.”

The water is continuously treated within the recirculatory system once it reaches the hatchery. An astral sand filter, filled with TMC glass filter media, removes particulate matter down to 20 µm. A TMC P6 ultra violet sterilising unit, a 30-liter biological filter, a 25 and 10-µm cartridge filter and 5-µm filter socks are also part of the system.

To maximize biosecurity the hatchery implements rules and policies, such as restricted staff entry, sanitizing before entering the algal culture room and before handling all live stock, sterilizing equipment, biosecurity foot baths upon entry, using lab coats and gloves during all stages of algae and larvae handling, histological sample analyses, and using autoclaved seawater where possible for gamete storage and algal culture.

With the hatchery newly established and this year’s funding only for purposes of establishing successful culture protocols for the species, ongrowing methods haven’t yet been confirmed. But through the hatchery’s strong links to academic professors from Plymouth University, areas such as stocking density, location and ecological impacts will be addressed soon, says Harvey. Handling and processing will also be confirmed once the hatchery is reliably producing spat.

Sustainable future

Hatchery-reared scallops will fulfil a gap in sustainable seafood sources, allowing people in Plymouth and elsewhere to purchase such seafood and enjoy it, knowing they have contributed to the conservation of a local species.

Within the next few months, the hatchery will be trialling new ways of conditioning and inducing spawning. Staff will also be investigating the scallops’ diet to ensure that all essential fatty acids are delivered during conditioning and larval development.

“We’re really excited for the year ahead,” says Harvey. “The hatchery has been up and running since May. Since then, we’ve managed to successfully fertilize eggs and rear larvae to 18 days post fertilization, where they developed an eye spot and were getting close to settlement. Due to having an initial low number of eggs, 100 percent mortality occurred on Day 18. This is, to our knowledge, the furthest through their lifecycle that a hatchery has achieved in the UK. It was an enriching learning experience and we’re now well equipped for our next batch.”

“Aquaculture is developing rapidly and for a good cause,” says Melanie Kruger, communications officer at Ocean Conservation Trust. “It can allow natural populations to thrive while delivering a sustainable source of nutrient-rich food for an ever-growing population. I’m really looking forward to seeing the hatchery techniques develop.”

Print this page

Advertisement

- Nordic Aquafarms responds to lobby group’s ‘misleading’ claims

- Norwegian researcher seeks to achieve ‘ideal tank’ for RAS