Features

Restocking

Herring and Oil Don’t Mix

January 13, 2015 By Heather Wiedenhoft

When the Exxon tanker went aground in Prince William Sound

When the Exxon tanker went aground in Prince William SoundFor herring, the spill couldn’t have come at a worst time, since the fish were starting to make their way into the Sound to spawn. Oil can have a devastating effect on spawning populations, as evidenced in the Cosco Busan oil spill in San Francisco Bay in 2007; herring eggs near the spill were almost all dead or deformed.

Prior to the Valdez spill, herring populations in the Sound had been increasing, with record harvests (up to 121, 000 metric tons) documented in the late 1980s. However, four years after the spill a dramatic collapse of the fishery occurred (only 30,000 metric tons recorded) in 1993. Since then, the population has remained depressed, fluctuating between 10,800 and 32,500 metric tons annually.

Among those affected by the crash were Alaskan coastal communities whose subsistence fisheries for herring as food and bait for troll fishing predate recorded history. Also hard hit was the large commercial industry for herring fish meal, bait, and food (including roe, a delicacy in Japan). In addition to their commercial and subsistence value, the marine ecosystem depends on herring to provide a key link between primary producers and larger animals in the food web.

Interestingly, while the Prince William Sound population has yet to fully recover (the herring fishery in the Sound has been closed for 15 of the 21 years since the spill) the Pacific herring population just outside the Sound continues to support a large commercial fishery.

So far there are still no real answers to the decline, and experts cannot even agree on the exact cause – instead pointing to several related factors rather than one limiting agent.

Causes and Solutions

What is uniquely disturbing about the Prince William Sound herring population is that, while many herring stocks have experienced collapses world-wide, herring are more likely to recover after reduced or zero levels of harvest compared to other fishes that decline due to fishing.

Some areas that concern researchers in Prince William Sound are the growing whale and salmon populations, and outbreaks of Viral Hemorrhagic Septicemia (VHS) in fish. Data from recent studies also points to a problem with recruitment of juvenile herring.

As Project Manager for Prince William Sound Science Center, Dr. Scott Pegau explains that even small adult populations, like in Southeast Alaska’s Sitka Sound, can produce many offspring and large recruitment numbers….enough for a robust fishery in years to come. Factors such as predation, food availability, and currents causing larval drift may be limiting the juvenile herring population in Prince William Sound. But there is still hope. According to Peg au, “A single large recruitment event (about 80 million fish) may be able to increase the adult population to a level where future large recruitment events occur, and…. “the rapid increase in adults may cause new spawning grounds to be used and therefore increase the possibility of retention of larvae leading to strong recruitment.”

Possible solutions

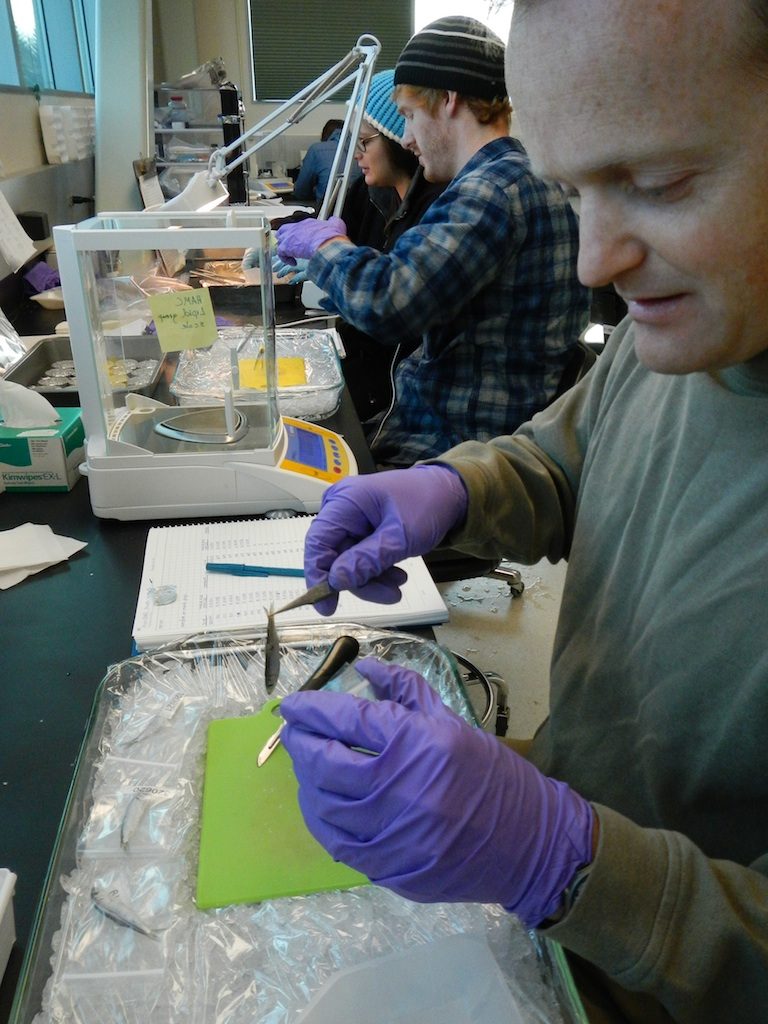

The next question to be answered is how to best address the situation….with studies even looking into the feasibility of starting a herring “aquaculture” program in Alaska. The studies are based on the success of the Japanese herring enhancement projects started in Hokkaido through the Japan Aquaculture Association (also on this website and in the print edition of the Jan/Feb 2015 issue.)

Would it be possible to use techniques like those in Japan in Alaskan waters, and artificially stimulate the herring population? This was one of many questions Japanese fish culture experts as well as North American aquaculture experts were brought in to answer. As consultants, experts were not only considering if it could be done, but also if it should be done, namely: What are the implications of aquaculture for wild fisheries? And what would Alaska stand to gain or lose from a herring aquaculture, or “enhancement program”?

“The idea is controversial”, said Dr. Doug Hay, a Scientist Emeritus with UBC Fisheries and Oceans Canada and an expert in the field of biology and ecology of herring. He points out that … “while technically possible, a program like that could fail on any number of biological levels.”

First, the practicalities of a massive herring operation within the boundaries of Prince William Sound, which Hay estimates to be about 100 metric tons carrying capacity, but he adds, “carrying capacity for herring has changed in Prince William Sound due to pink salmon hatcheries and production.”

He sees the continental shelf as the ultimate limiting habitat factor, and explains, “In most areas of the North Pacific, the adult component of large herring populations move to shelf waters to feed in the summer. Presumably this also occurs in the water adjacent to Prince William Sound. Access to the adjacent shelf waters probably would expand feeding opportunities by a factor several times greater compared to the potential to feed only within the Sound.”

Critical factors

Other critical components for aquaculture success are seen as the degree to which adults display homing or site fidelity to area of origin and whether large numbers can be mass marked and recovered to discover contribution to spawning population. There’s also susceptibility of cultured fish to pathogens, and production costs.

If a hatchery operation were to be developed in Alaska Hay proposed a modification of the Japanese practices, opting for a less controlled environment. He recommends natural incubation in cargo containers or “oil-tanker hatcheries” (an ironic use of resources), suspended in the sound with good channel flow, here letting the eggs develop natural resistance to parasites/viruses in the ecosystem. To ensure the juveniles make it through that first tough winter, Hay recommends keeping them in the hatchery through their first summer and fall.

And he emphasizes that a key element is to minimize stress during re-location to reduce chance of disease and pathogens.

But aquaculture is a two part program – rearing, and then monitoring the catch.

In the United States the FDA will not allow fluorescent marking in fish for consumption so Alaska would need to develop a marking system for hatchery herring, and instigate a monitoring program to survey huge amount of fish for markings to be able to define success. “It could take a couple years just to come up with a tagging system for herring,” Hay warns.

So it seems it could be done, but should it be done?

First is the feasibility: In 2001 the lowest estimate to produce one million fish (the minimum to be released) was about 19 cents per fish. This year the price for herring dropped to about 21 cents per kilo.

And ethically, can enhancement create new problems? There is always the possibility of a negative ecological impact on wild fish through competition, alterations of genetic diversity, and increased disease.

Competition from aquaculture has become a driving force for change in the management of wild fisheries, as seen with the Alaska salmon populations.

When asked if they thought a herring enhancement program like Japan’s could work in Alaska (specifically Prince William Sound), the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Research Council researcher Toyomitsu Horii replied: “I think appropriate management of fisheries and habitat is more important for herring stock conservation, not only in your country but also in Japan. It’s my personal opinion.”

Dr. Shingo Hamada, Project Researcher, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, added: “it would be very expensive. In my opinion, tightening fishing operations (esp. seine nets) by limiting the number of licenses, limiting the fishing operation sites, shortening fishing period, and shrinking total/regional TAC would be enough for Alaska for now, rather than so much money spent in stock enhancement operations.”

— Heather Wiedenhoft

Herring buyback another option

A recently resubmitted proposal to the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustees Council recommends a herring permit buyback initiative as a restoration effort. Given the current market trend for herring and herring roe the buyback may make sense. Fishermen are reporting a possible advance of $150 per ton for roe this season, and while it is expected to go up, it is unlikely to match the 2013 price of $600 per ton. Part of the reason is a flooded market from last year’s harvest, and part of the reason for the flooded market is a cultural shift in Japan, where the roe is sold.

Many permit holders were in support of the buyback proposal. The money could be used to buy individual fishing quota or other salmon permits, thus giving the former herring fishermen an opportunity to turn an inactive herring permit into some real fishing time., and giving the marine ecosystem time to recover, leaving all the herring in the water for the many predators that rely on them.

Print this page