Features

Profiles

Monumental task: Centuries-old restoration efforts in Penobscot River, Maine

On August 24, 2016, President Barack Obama used the Antiquities Art to declare 87,563 acres of mountains, forest and rivers as Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument. The monument is located in northern Penobscot County, Maine. This includes a large section of the upper East Branch of the Penobscot River known as a significant piece of this extraordinary natural and cultural landscape.

September 6, 2018 By Eric Hendrickson

Charles Atkins In August 24

Charles Atkins In August 24The extraordinary significance of the Penobscot East Branch River system has long been recognized. A 1977 Department of the Interior study determined that the East Branch of the Penobscot River, including the Wassataquoik stream, qualified for inclusion in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System based on its “outstandingly remarkable values as a nationally significant resource.”

President Obama’s proclamation discussed how the removal and retrofitting of downstream dams would enhance the integrity of the Penobscot East Branch river system and provide opportunities for scientific study of the effects of the restoration on upstream areas within Katahdin Woods and Waters. It will also allow the federally endangered Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) to return to the upper reaches of the river known in the Penobscot language as “Wassetegweweck,” or “the place where they spear fish.”

By the 1890s the upper East Branch of the Penobscot River was developing as an area of wilderness salmon sport fishery. In 1903, a report from the Bureau of Fisheries declared the Penobscot River as the most important salmon river in New England with fish being taken primarily by weirs, gill nets and trap nets.

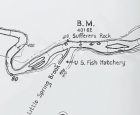

Within the monument, the East Branch of the Penobscot once played an important role in Atlantic Salmon fisheries. A man named Charles Atkins played a pivotal role in the hatchery development on the river. The salmon hatchery’s location was at the mouth of Little Spring Brook across the river from Sufferers Rock, which is a ledge outcrop about 14.05 miles downstream from Grand Lake Dam. You can still find the original aluminum marker with an elevation of 402 feet, as it was part of a 1908 water survey of the Penobscot watershed done by the USGS looking for possible locations for dams. Atkins was a New Englander, born in New Sharon, Maine, on Jan. 19, 1841, attended Bowdoin College and was considered to be a truly visionary fish biologist of his time.

Hatchery births

Atkins and Nathan Foster were the first Maine Fisheries Commissioners. In their first report on January 1868, they stated that, “the salmon is suffering from neglect and persecution.” The U.S. Congress then followed the states’ lead, creating the U.S. Commission on Fish and Fisheries on February 9, 1871 – a precursor to the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Spencer Baird was appointed its first commissioner, and among his first directives were to conduct studies on the decline of coastal and inland food fishes and methods of fish culture. Baird turned to Atkins for his expertise and directed him to locate a suitable site in Maine to raise Atlantic salmon.

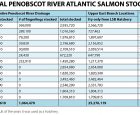

In 1871, Atkins opened the Craig Brook Hatchery, which is still in operation today. In the beginning, Atlantic salmon eggs were taken only from the Penobscot River, from 1871 to 1875, and then again in 1879 to 1919. In addition to the hatchery at Craig Brook, the federal government opened Maine hatcheries at Bucksport in 1872, Sebec Lake in 1873, Grand Lake Stream in 1875, Green Lake in Dedham in 1892, Upper Penobscot in 1903, and the Salem Feeding Station in 1941.

Significant enhancement

Atkins opened the Upper Penobscot Auxiliary Station (Little Spring Brook Hatchery) in the fall of 1903, and it operated until spring of 1916. Eggs were collected by fishermen in the lower Penobscot River.

At the Craig Brook Hatchery, people used the dry method of fertilization for the eggs. The hatchery operated each year from October or November through May or June. Eyed eggs from Craig Brook were taken by train to Sherman, transferred to another train to Patten, and then by wagon for eight miles to the Charles McDonalds Camps, now called Bowlin Camps on the river. There, the eggs were taken by wagon across the ford and several miles downriver to the Little Spring Brook facility – where they stay until the eggs hatched into fry. In May or June, all of the fry were released into the East Branch – the facility did not have the ability to produce food or feed the fish so they were released as soon as the egg sack was gone. The fry were carried by buckets down river in canoes carried in buckets or by wagon using the East Branch Tote Road. They were generally being released along the way.

Records show that the vast majority of salmon stocked in the Penobscot drainage each year from 1904 to 1916 were produced at the Little Spring Brook facility. During that period, 25 million fry were released into the river, accounting for 99 per cent of all fry released into the Penobscot River System. The hatchery was closed in 1916 for unknown reasons; it may have been weather, floods, fire or disease that closed the facility, but we will never know for sure.

After 1919, things went downhill quickly for the salmon population in the East Branch of the Penobscot River. In 1919, salmon eggs from Canada began to be used because of “uncooperative” Penobscot River commercial fishermen who were no longer willing to sell eggs. Penobscot salmon runs and the fishery continued to decline in the 1920s and ‘30s after Canadian eggs replaced Penobscot River eggs, until they were almost non-existent.

Plan of action

Efforts are currently being renewed, thanks to a multiparty public-private project, to reconnect the Penobscot River with the sea and continue to work toward restoring a self-sustaining population of sea-run Atlantic salmon to the excellent clear water spawning and nursery habitat of the East Branch and its tributaries. Perhaps, the recent efforts were inspired in part by those early conservation efforts, but we will never know.

Obama’s declaration of the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument will protect the watershed while providing an opportunity for scientific research on the effects of the restoration on the upper river area. In time, the return of the federally endangered Atlantic salmon will complement the exceptional cold water native brook trout fishery that already exists within the monument.

Eric Hendrickson is a retired science educator and former Maine Guide/Outfitter from Presque Isle. He has published over 100 articles about natural history in various publications. In 2002, he was awarded with the certificate of merit by the National Speleological Society. He is an avid explorer of the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, where he enjoys discovering the historical, cultural and national history locked up in the land.

Print this page

Advertisement

- IAA bankruptcy no impact on Nordic Aquafarms projects: CEO

- Challenges, solutions for Tanzania’s African catfish industry