Features

Business Management

Disease Management

Recirc

Sustainability

PiIot farm fails despite best efforts

Closure points to broader challenge of ensuring economic viability in RAS shrimp farming

December 13, 2019 By Liza Mayer

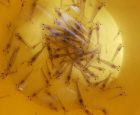

Dozens of shallow tanks stacked to the rafters in the production area would typically contain 500 lbs of juvenile shrimp swimming in 12 inches of water.

Dozens of shallow tanks stacked to the rafters in the production area would typically contain 500 lbs of juvenile shrimp swimming in 12 inches of water.

The news that the farm is shutting down came as a shock.

During a recent visit just three weeks prior, land-based shrimp farm Berezan Shrimp Co in Langley, BC, even shared good news with Hatchery International: “Our production – we’ve been hitting all of our numbers and everything else. We’ve conquered challenges and we’re moving on to the next thing,” says general manager Warren Douglas.

The farm was on a hiatus during a visit by this writer in late August. There were no shrimp in the tanks, and a staffer was hosing down some containers. “We’re given an opportunity to dry the farm out and make some upgrades. Once we’ve put this back together and fire this back up, probably on November 1, the larvae will go into the nursery. The crop that comes in November will be ready in February,” he says.

There was no reason to doubt Douglas’ confidence in re-opening the farm. After all, the Infectious Hypodermal and Haematopoietic Necrosis virus (IHHNV) detected in its Litopenaeus vannamei (whiteleg shrimp) crop could be eradicated successfully in most cases.

In early September, however, Berezan Shimp announced it was shutting down production, perhaps forever. What happened?

The beginning

Berezan Shrimp had big dreams when it put its first shrimp in the water in November 2017. It once told the Vancouver Sun that it hoped to build “several 2,500-tonne commercial-scale facilities” in Chilliwack, a city east of Vancouver, once it has conquered the technology, “hopefully by 2024.”

As a land-based operation, the farm has earned accolades from environmental advocates. A freshwater well in the property supplies the water it needs (salt is added to it later) and 99 percent of that water recirculates.

From the outside, the 20,000-square-foot farm looks like an aircraft hangar. A few meters from the entrance is its production area and around the corner is the nursery. The nursery’s residents – 0.003-gram post-larvae (PL) from Texas – arrived once a month at the Vancouver International Airport. They travel roughly 50 km to the farm, where they are acclimatized for six or seven hours. This period used to be 12 hours when the farm first started, says Douglas, “but now we’ve kind of perfected our technique quite a bit.”

Dozens of shallow tanks are stacked to the rafters in the production area. If the farm had been running, each would have contained 500 pounds of juvenile shrimp swimming in 12 inches of water. These would have produced a maximum of about 6,000 to 7,000 lbs. of shrimp per month.

“The traditional farms are a hectare in size normally and they’re a meter to two meters of water deep. If we were a hectare, [our water usage] would be less than 30 percent of the required water of the traditional raceway but have three times the production,” says Douglas.

The “super-intensive stacked raceways” in the farm are an invention of Addison Lawrence of Texas A & M University. Aside from requiring less water, stacked raceways require less area compared to those traditionally used in aquaculture, which are laid side by side. The invention received U.S. patent in December 2012. Lawrence’s prototype even caught the attention of The New York Times about a year prior.

In an article dated November 5, 2011, the publication quotes the scientist saying that his innovation “makes it possible to produce up to one million pounds of shrimp annually per acre of water, compared with the 20,000 pounds produced by natural ponds, and the 50,000 pounds produced by the original raceways system.”

Douglas says the Langley farm had proven those numbers out. “If you extrapolate it out, based on the number of square meters of water that we have on this farm, we’d be hitting those numbers.”

But as a pilot operation, the farm’s production of roughly 72,000 lbs. a year “isn’t even a toe-depth” compared to the 1.8 billion lbs. of shrimp being imported into North America every year, Douglas says.

The recirculation technology was developed in-house. Berezan Shrimp has a team of nine people, of which five are biologists, with 60 years of combined experience in recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS). In the 22 months since the farm started operations, 16 batches of PL have been stocked in the nursery and it was only in the thirteenth batch that the team finally hit the “sweet spot” in the biofloc system.

“It’s a balancing act between keeping the biofloc at a healthy level, making sure you don’t underfeed, making sure you don’t overfeed; the probiotics, temperature. Basically keeping the shrimp as happy as they can be in there and that really propelled them going forward into the production system,” Douglas says.

Matt Stone, a team member, brought to the table his expertise in live feeds and larval nutrition development. As the go-to guy for emergencies at the farm, it wasn’t unusual for him to be woken up at 2 or 3 in the morning if something goes out of range.

Stone recalls the tough early days, when the team experimented with water temperature salination and nutrition, among others. “It took us a long time to fine-tune our biofloc system,” Stone says. “From batch 13, we really had a good amount of feed and some good, healthy biofloc going. So the animals that actually left the nursery at that stage were the biggest (at about 0.15 grams) they’ve ever been, and every batch after that had been bigger and bigger.”

“The increased size gives them a bit of a jumpstart when they got stocked into production (tanks) because obviously the bigger the animals are when they get into production the better they’re going to do,” Stone continues. “So that was a bit of a turning point for us and basically every batch from batch 13 has been leaving the nursery at a bigger size. So we’re starting to see the benefits of that.”

Despite those milestones, Douglas notes that the advances in their biofloc aren’t scalable. “The biofloc water is at its most stable but it’s not scalable. We can’t take biofloc into the production tanks. It just doesn’t work with the recirculating system.”

Disease mitigation

As a closed system, the greatest strength of a land-based farm could also be its greatest weakness. Disease epidemics, either from imported animals – one that is transmitted down from the mother to the progeny – or from the outside environment due to poor management, can quickly decimate production.

“There is a common falsehood that somehow RAS systems are immune to disease. I have seen very few RAS systems remain disease-free. In many systems, infection disease enters either via the water supply, from incoming juveniles, from contaminated transportation equipment or from imported live feeds. The best defense against infection disease is for the animals to have a robust immune system. Select disease-resistant animals and vaccinate as required,” says Brad Hicks, an experienced net pen farmer who installed the first RAS salmon system in B.C. 23 years ago.

“Atlantic Sapphire had a problem with furunculosis, a common bacterial problem in Atlantic salmon for which there is an effective vaccine. The furunculosis bacteria was suspected to have come from the incoming water supply. It is my understanding that the fish had not been vaccinated for furunculosis because at the time the operators thought they would be immune from infectious disease because they were using RAS,” he adds.

B.C.-based industry consultant Samuel Chen believes sanitizing RAS farms from a virus is “definitely easier” than sanitizing a pond because the former is a closed system. “But when a pathogen gets into a closed system, it may be an even greater risk for the animals inside because of higher densities. That’s why biosecurity and controls are so important in RAS systems.”

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) restricted imports of live whiteleg shrimp from Texas and Florida on July 4, 2019 because of the detection of IHHNV in those populations. CFIA confirmed with Hatchery International on September 14 that Berezan Shrimp remains under quarantine.

“We received the virus from our PL supplier in Texas,” Douglas says when reached by phone on the day the news of Berezan Shrimp’s closure broke. “The virus is really tough to get rid of once it gets into your building.”

Hard truths

But getting hit by a virus wasn’t the sole culprit for the RAS shrimp farm’s eventual demise. Douglas notes: “Actually, financially, the farm was not paying its own bills. It’s a business decision at this point. Certainly because we’ve cracked the code, we know how to acclimate the PLs, grow them to market size and they have fantastic quality. But there’s just too much overhead for the pilot. Number one cost is labor; our number one cost should be feed.”

“It’s a chapter in pioneering,” he adds. “We wanted to produce a safe, sustainable, quality and affordable product. We got three of the four. We felt that our cost of production was going to be a burden for us to get major traction. Our cost of production was too high. Our entry cost for the shrimp was going to be too high.”

Understanding production costs is key to a profitable and sustainable RAS venture, says Brad Hicks. “This is RAS. Cost of production is greater than the value of the crop. RAS works for lot of things but you need to understand production costs very well and you need to know the market very well. If you don’t know your production costs or your markets you are just gambling against a stacked deck. And the outcome is always the same – failure.”

Print this page