Features

Breeding

Profiles

Restocking

Dry spell: North American hatcheries dealing with drought

July 12, 2019 By Matt Jones

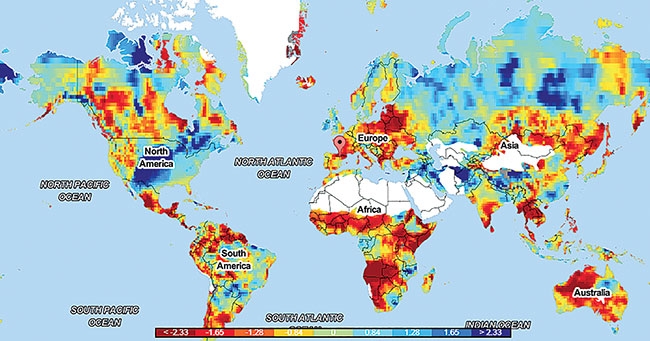

This map shows drought conditions around the world as of March 2019 Droughts can be devastating disasters

This map shows drought conditions around the world as of March 2019 Droughts can be devastating disastersDroughts can be devastating disasters, with pronounced impacts on people, farming and ecosystems. The impacts can be doubly severe for water-based operations, such as hatcheries.

According to drought monitoring services, much of western North America has been suffering from drought conditions recently, and even as water levels in long-suffering areas such as California have started to recover, hatchery operators wonder how long it will be until the next big one.

California

The most recent California drought lasted over seven years until earlier this year. In 2014, water levels in some parts of the Sacramento River became so low that officials were forced to transport young salmon to the Pacific Ocean by truck. Mark Clifford, environmental program manager for trout and salmon hatcheries with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, says the drought was unprecedented and the driest years in the state’s historical records.

“It was a cumulative effect of several years where the snow pack wasn’t adequate to refill the reservoirs, precipitation statewide was lacking, and the reservoirs were drawn down,” says Clifford.

After examining the state’s extensive measurements for water temperatures, flows, tides, diversion operations and even lunar cycles to see if there would be major population effects, the state pursued a number of initiatives to address the challenge. Portable recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) were built and representatives of certain populations, such as coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch), steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and McCloud River redband trout (Oncorhynchus. m. irideus), and California golden trout (Oncorhynchus aguabonita) were rescued.

Two of the state’s largest hatcheries, the San Joaquin Hatchery and the American River Hatchery, had to be depopulated after summer temperatures became so high that they knew they would lose all the fish. Releasing all of their inventories into the wild was a tough blow and has made it challenging to get back into the production cycle.

While the state has undertaken infrastructure improvements, Clifford feels the state is far from being completely resilient to the potential effects of future droughts. Proper preparation, he notes, requires not only political will and capital, but also forward planning and strategy.

“Let’s say that somebody did suddenly offer up tens of millions of dollars, now you have to line out the contracts, and the engineering and the subcontractors,” says Clifford. “You really need to think about something that isn’t happening yet for two or three years and lay out all the groundwork to get projects accomplished. To suddenly be in the middle of a drought, and then provide funding for it, is inadequate. You need advanced planning for infrastructure, in addition to the capital.”

British Columbia

The Chapman Creek Hatchery has long faced challenges due to flow rates and water levels (see our story on this on Hatchery International Nov/Dec 2017). Earlier this year, it was announced that the hatchery would not keep fish on site during the summer months as another drought is expected. Hatchery manager Simon Grant says keeping salmon in waters as warm as they are expected this summer would be tantamount to animal cruelty.

“We’re not able to meet the standards required for salmon survival in the summer time,” says Grant. “They’re in 23-degree-water and that is just not acceptable. We should not be holding fish at that temperature. Anything above 16 degrees starts messing with them.”

The hatchery typically holds 57,000 coho on site over the summer, but this year it has made arrangements with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans to move them to the Capilano Salmon Hatchery. There simply isn’t enough water to ensure flow rates and proper temperatures.

“Our system, the creek, is attached to Chapman Lake, which feeds the Sunshine Coast Regional District (SCRD) drinking water,” says Grant. “It’s looking pretty dry out there already. We’ve had a really dry winter, and we didn’t get much snow.”

Such issues are becoming more and more common in the province – Grant cites the example of the nearby construction of the Sooke River Jack Brooks hatchery, a $1-million facility meant to respond to water issues (see our story on Hatchery International Jan/Feb 2019).

“What you’re going to start to see is any kind of hatchery that’s attached to drinking water is in trouble, because it’s getting so dry,” says Grant.

To attempt to address the issues, the Chapman Creek Hatchery has applied for a $6.5-million grant to the BC Restoration Fund with a proposal to rebuild the 30-year-old facility into a RAS facility. They have also prepared a document for the SCRD to give them ideas on water use and education, and are pushing them to start a public education campaign. Residents in SCRD commonly use 650 liters of water per day, about 400 liters more than the national average.

“I want to turn it back on the community and say, ‘Look, you guys need to start throttling back on your water use,’” says Grant. “I know a lot of people are doing that, and a lot of people are aware of it, but we’re still up around 600 plus liters a day and that’s the big thing.”

Alaska

Even as far north as the Crystal Lake Hatchery, near Petersburg, Alaska, drought conditions caused significant uncertainty and concern. In the middle of a rainforest, the area usually sees an average of 150 to 160 inches of rain per year but saw roughly 50 fewer inches in 2018.

“At one point they told me we had 50 days left if it didn’t rain,” says Bill Gass, production manager with the Southern SE Regional Aquaculture Association. “It did rain and we managed to get through that season. We didn’t have to make any major production changes. We just knew that we were starting to move down to levels we hadn’t seen before.”

After unusual dryness in February and March, April saw renewed precipitation and, as of press time, the drought’s impacts on the hatchery appear to have been a one-year event. However, if drought conditions return and persist going forward, hatcheries could be at risk.

“If we no longer live in a rainforest we have a big problem, and I’m not exactly sure how we’re going to deal with that,” says Gass. “I’m not sure if the facility would remain viable at that point. This may sound strange to some of the readers of Hatchery International, but virtually all the production in Alaska is single-pass gravity feed – that’s a luxury that we’ve been able to enjoy. A lot of these are remote facilities out in the hinterland, on isolated islands and building large recirculating facilities just hasn’t been justifiable. But that’s probably the first thing we’ll start looking at if it turns out we have less water than we used to.”

Climate change at fault

When discussing the potential causes of these droughts, both Clifford and Gass are quick to note that they are not climate scientists and decline to speculate beyond their areas of expertise. Grant, while cautious of overusing the term and reducing its impact, is more certain.

“If you look at the historical trends on climate along our coasts, you’re definitely starting to see changes in that,” says Grant. “That now is moving further up the mountains, and we still get the same volume, it’s just not as regular. Throughout the year, you get the same amount of rain, but the patterns have shifted.”

A report published in May in the journal Nature outlines how researchers analyzed tree ring archives, confirming “that human activities were probably affecting the worldwide risk of droughts as early as the beginning of the twentieth century.”

Print this page

Advertisement

- Philippines university develops fry counter for small-scale hatcheries

- Hatcheries face climate change consequence