Features

Genetics Week

Research

shellfish

Alutiiq Institute makes strides in shellfish

Alaskan hatchery turned research institute is a hub for shellfish production and research

January 20, 2023 By Nancy Erickson

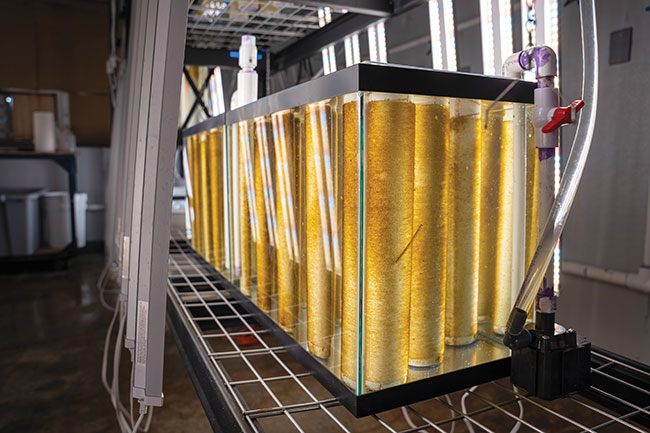

Following several weeks of nurturing in an APMI lab, tubes of budding kelp string appear ready for outplaning to aquatic farms.

(Photo: Southern Dipper Productions)

Following several weeks of nurturing in an APMI lab, tubes of budding kelp string appear ready for outplaning to aquatic farms.

(Photo: Southern Dipper Productions) It’s been said good often arises from the ashes of tragedy.

When the oil tanker, Exxon Valdez, ran aground in Prince William Sound in March 1989, it spilled 11 million gallons of crude in the ocean. The oil slick covered 1,300 miles of Alaska’s coastline and killed hundreds of thousands of seabirds, otters, seals and whales, resulting in one of the largest environmental disasters in U.S. history.

From the billions in settlement monies paid by Exxon Shipping Company arose organizations and institutions dedicated to restoring the damaged environment and gaining first-hand knowledge of the state’s unique marine ecosystem.

One such institution is the Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute (APMI) in Seward, Alaska.

Built by the State of Alaska’s Department of Fish & Game from criminal settlement funds resulting from the Exxon Valdez oil spill, the centre initially opened as the Alutiiq Pride Shellfish Hatchery with the purpose of recovering the Alutiiq tribes’ subsistence resources and producing oysters and clams for the aquatic farm industry. As the research focus broadened, the centre rebranded into the APMI.

APMI is a division of Chugach Regional Resources Commission (CRRC), an intertribal consortium of seven Alaska Native Villages in the Prince William Sound and Lower Cook Inlet region. The Alutiiq people, also known as Sugpiaq, are a southern coastal Alaskan Indigenous people inhabiting the majority of this region. The villages’ strong cultural ties and rich understanding of natural resources and marine systems in the Chugach region allows insight to a deep knowledge base generally not readily accessible to other aquaculture facilities.

Jeff Hetrick

More than a hatchery

Located at the head of Resurrection Bay, a walk through APMI’s doors reveals a lot more than researchers propagating shellfish for aquatic farmers.

“We do much more now than just hatch oysters,” said Jeff Hetrick, mariculture director. “We’ve raised red and blue king crab, geoducks, clams, oysters, littleneck clams and sea cucumbers, to name a few. We’ve also cared for salmon, halibut, herring and octopus for research projects.”

“We provide juvenile shellfish seed and kelp string with partners statewide,” he added. “We’re presently raising abalone and sea cucumbers for Southeast Alaska projects, and clams for our tribal communities’ enhancement projects. All our research is applicable statewide.”

Shellfish populations have been on the decline for many years, according to Hetrick. Researchers at APMI are exploring reasons for the decline and at the same time, taking steps to provide harvest opportunities for member tribes.

“Having control over the whole life cycle, from spawning to harvest, allows us to complete the life history of culturally important species in our region, such as littleneck and butter clams as wells as cockles,” explained Hetrick.

New species to Alaska have also been identified. APMI staff has recently been focusing on a soft-shell clam (Mya arenaria) due to the species’ ability to thrive in the current environment and also because of its fast growth in the hatchery and on local beaches.

“This growth may prove to be an adaptation strategy for the loss of hard-shell clams and offer a potential mariculture species for Alaska,” said Science Director Dr. Maile Branson.

Another exciting project APMI researchers spawned this year is the culturally significant black katy chiton (Katharina tunicata), locally known as “bidarkis.”

Chitons are marine molluscs with oval shapes and shells divided into eight dorsal plates. These chitons have traditionally been an important subsistence food for more than 100 years to Alaska natives in the communities of Port Graham and Nanwalek in Kachemak Bay on the southern tip of the Kenai Peninsula. However, concern has been growing among community members who have observed a decline in the size and total number of animals in the previous 10-15 years.

Little is known about the life history of chitons. APMI researchers hope to develop techniques to produce them in the hatchery and outplant on beaches, tracking their growth, survival and reproductive capacity so community members in remote tribal villages can continue to subsist on a species of their preference since time immemorial.

Another recent project involves developing techniques for raising blue and red king crab juveniles. APMI staff were integral in the Alaska King Crab Research, Rehabilitation and Biology (AKCRRAB) Program, working with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Alaska Sea Grant, amongst other key partners, culminating in over five years of data studying growth, behaviour, predator interaction and habitat preference of juveniles once released. Researchers are optimistic the data will be used for improving localized populations, said Dr. Branson.

The future of crab enhancement research had been on hold for several years awaiting legislation from the State of Alaska allowing shellfish enhancement, which passed in 2022.

“We’re waiting for the Department of Fish & Game to propose regulations so we know what it will take to move ahead,” Branson added. “We’ve been laying the groundwork for a project that would involve a local juvenile crab release in 2024.”

Keeping oceans healthy

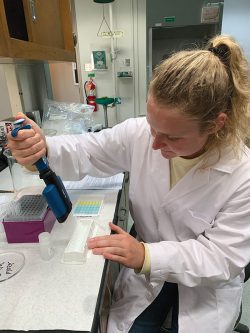

APMI staff biologist, Annette Jarosz, runs an Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay for the detection of shellfish toxins. Ingestion of shellfish containing the toxin can be potentially fatal.

(Photo: Maile Branson)

From direction of CRRC’s board of directors, researchers at APMI began sampling and processing dissolved inorganic carbon in 2013 as a measure of ocean acidification through APMI’s Ocean Acidification Research Lab – the first near-shore station in Alaska at the time, but now part of a worldwide network.

Seawater in Resurrection Bay is continually monitored as a baseline and the Native communities in the Chugach region, as well as other partners around the state, continue to send water samples to APMI to determine acidification levels.

“Our tribal leadership felt the need to expand our shellfish enhancement projects into seafood safety and impacts climate change has on coastal residents’ food sources,” said Hetrick.

With that directive, Branson was added to the staff and expanded the science program to include Chugach Region Ocean Monitoring (CROM), incorporating a full suite of sampling including water chemistry, nutrients, phytoplankton, paralytic shellfish poisoning and harmful algae monitoring.

Alaska has specific species of planktonic algae that produce toxins that can be harmful to people, animals and surrounding ecosystems. These toxins can cause severe health problems when ingested and can be fatal. The APMI web site provides real-time data to the public to help determine the risk level for recreational and subsistence harvest of shellfish and other marine organisms.

“The key to all CRRC and APMI programs – CROM included – is the engagement of residents in our communities who collect the data and submit samples,” said Hetrick.

Kelp farming

Kelp farming is gaining in popularity among regional fishermen looking for opportunities during their off-season.

APMI is assisting with startup logistics by growing “seed” to outplant in their ocean-based kelp farms – experimenting with sugar, ribbon and bull kelp.

“We produced seed string for 10 research sites and five commercial farms in 2022 and expect demand to double or more every year for quite a while,” Hetrick said. “We know we can grow the string in the hatchery, but we’re now in the scaling and efficiency mode to insure we can meet the demand as it arises.”

Inside one of APMI’s modules is a series of two-by-15-inch plastic pipe wrapped with 200 feet of nylon twine inoculated with kelp spore solution. The string is monitored and controlled with temperature and light until plants germinate and are ready for shipment to farmers or test sites. At the site, the string is unraveled onto grow lines suspended between buoys approximately seven feet below the surface and monitored for six to seven months until harvest in the spring.

“It takes a lot of time and care to tend to the seed string for a couple of months but it is very rewarding to see kelp grow on the string,” said Michael Mahmood, APMI production manager.

Sights on the future

Divers harvest kelp on the ocean floor for the collection of sorus tissue. The tissue holds a cluster of plant reproductive bodies, which will be used in creation of kelp in the laboratory.

(Photo: Birds Eye View Advertisement)

Alaska’s mariculture industry is growing and ripe for expansion and investment.

NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service estimates U.S. aquaculture is likely to grow at least 250 per cent over the next 10 years. NOAA posits the growth could be even higher, as stated in the report, “An Approach to Determining Economic Impacts of U.S. Aquaculture.”

APMI has doubled its staff in Seward over the past year and will continue to grow as new opportunities and challenges arise with the expansion of mariculture in the state and changing ocean conditions.

“We see ourselves continuing to be a leader in shellfish research in Alaska and North America, not only with hatchery technology but in clam enhancement and restoration,” said Hetrick.

Print this page

Advertisement

- Superworm larva meal improves gilthead seabream immune system

- Optimal hatching condition protocols on B. altianalis seed production in Uganda